ALT

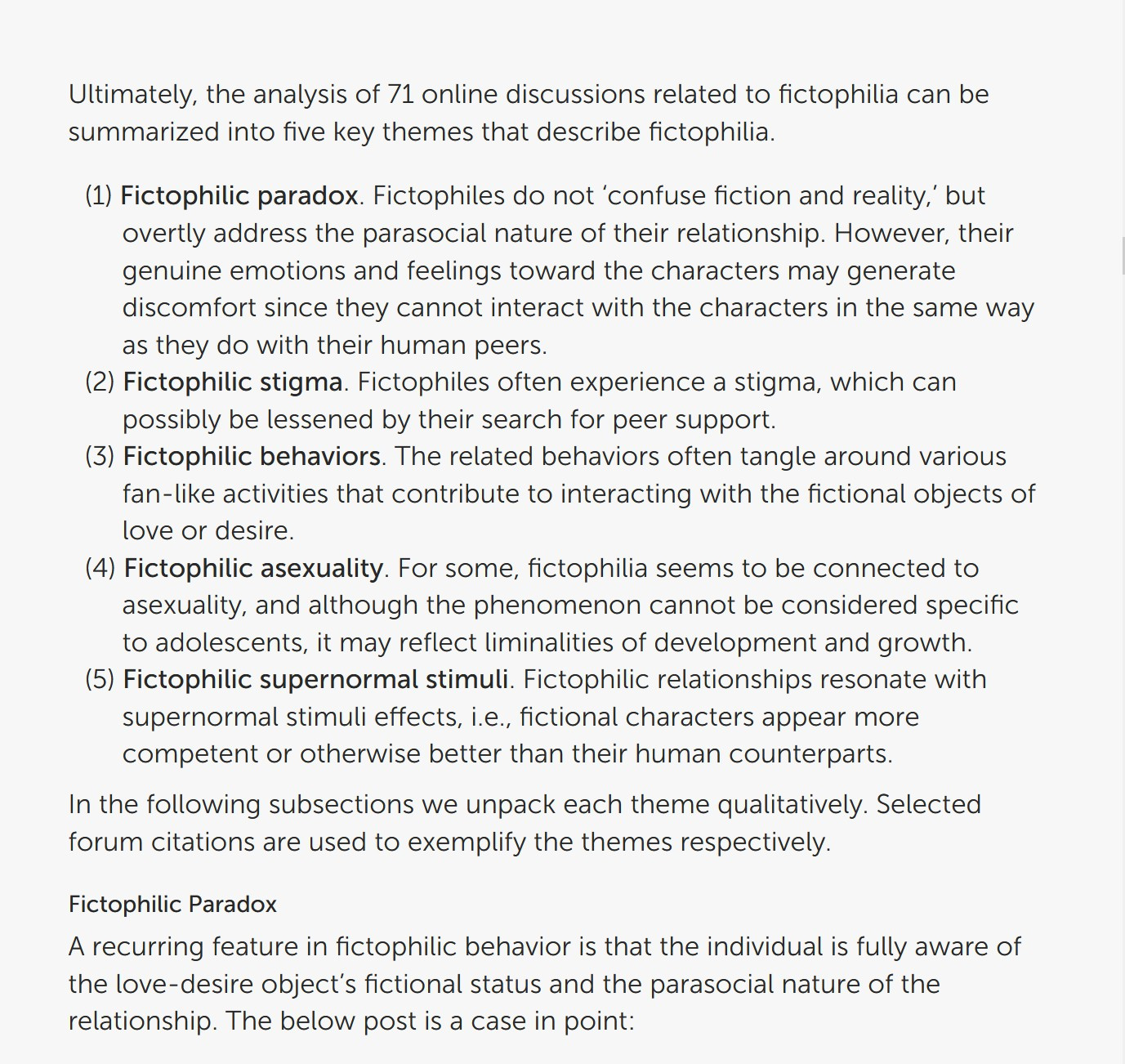

![In this section we briefly address the five themes analytically. The final section then looks at fictophilia in cross-cultural theoretical perspectives and Japanese media psychological literature in particular.

Fictophilic Paradox

Our results included few indications of those experiencing fictophilia to ‘confuse fiction and reality’. Rather, they were fully aware of the fictional nature of the characters to which they were attached. Unlike in mental disorders like erotomania where the individual has an imaginary belief of a mutual relationship that does not exist (e.g., Kennedy et al., 2002), fictophilia does not usually entail such hallucinations but consists of the person’s self-aware feelings toward a non-organic construct that they know to be ontologically diverse (e.g., Livingston and Sauchelli, 2011; Karhulahti, 2012). At the same time, however, the intensity of emotions and feelings in fictophilia may lead to fantasies of the character in question ‘loving back’ or ‘becoming an actual companion.’ Evidently, such a genuine relationship is practically impossible and cannot materialize – and being aware of this, as fictophiles tend to be, constitutes a fictophilic paradox in which the coexisting awareness of fictionality and a wish to deny that produce emotional confusion. The above echoes Cohen’s (2004) earlier work that found attachment styles to be linked to the intensity of parasocial relationships by the measure of separation distress from favorite television characters, thus “parasocial relationships depend on the same psychological processes that influence close relationships” (p. 198). Adam and Sizemore’s (2013) survey study produced similar results, indicating that people perceive the benefits of parasocial romantic relationships similarly to those received from real-life romantic relationships. The genuine emotions and feelings that surface in fictophilia support and advance the above earlier findings – in fictophilic relationships, [cuts off]](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_fullsize/plain/did:plc:b4xvvsmocjzn3z2xpcxc2sbt/bafkreicdz4c2rlcyc4qkwb6ppjw2sytj4ll7uk647w3xjyn3bmqtd24sji@jpeg)

ALT

![The otaku, Saito argues, are in fact more conscious and analytical of the nature of their (potential) romantic-sexual emotions or feelings than those who problematize them. This analytical consciousness allows the otaku to cope with their fiction-related emotions and feelings in elegant ways that may be difficult to grasp from the outside:

while they do not in any way ‘confuse fiction with reality,’ they are uninterested in setting fiction and reality up against each other … This means not just falling in love and losing oneself in the world of a single work, but somehow staying sober while still indulging one’s feverish enthusiasm … ‘What is it about this impossible object [that] I cannot even touch, that could possibly attract me?’ This sort of question reverberates in the back of the otaku’s mind. A kind of analytic perspective on his or her own sexuality yields not an answer to this question but a determination of the fictionality and the communal nature of sex itself. ‘Sex’ is broken down within the framework of fiction and then put back together again (pp. 24–27).

We may recall here those online discussions that dealt openly with questions of ‘naturality’ or ‘normality’ related to fictophilia, i.e., whether longitudinal romantic-sexual emotions and feelings projected on fictional characters should be considered abnormal, unnatural, or even unhealthy (‘It’s just so weird to me and I don’t think this is normal?’). From Saito’s viewpoint, such concerns for ‘naturality’ or ‘normality’ in fictophilia and the emotions and feelings involved may be calibrated as follows: how does the individual understand ‘real(ity)’ and where is their object of attachment (fictional character) located within that understanding?

Saito’s perspective forms an integrated context within which ontological distinctions are considered irrelevant in total. If an individual understands their fictophilic orientation as a prolonged unsuccessful attempt to build a bridge between two [cuts off]](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_fullsize/plain/did:plc:b4xvvsmocjzn3z2xpcxc2sbt/bafkreiailttr4542crzg44igz2hjc5onoxq333v7pfm5zivysxksj45mfu@jpeg)

ALT

This article is fantastically interesting 👀📚

'Fictosexuality, Fictoromance, & Fictophilia: A Qualitative Study of Love & Desire for Fictional Characters'

I think this discussion is what a lot of young fans may confuse when arguing 'fiction affects reality'

www.frontiersin.org/journals/psy... 🧵

'Fictosexuality, Fictoromance, & Fictophilia: A Qualitative Study of Love & Desire for Fictional Characters'

I think this discussion is what a lot of young fans may confuse when arguing 'fiction affects reality'

www.frontiersin.org/journals/psy... 🧵

TLDR;

infatuation with fictional characters has generally been seen as normal and unobtrusive for people who fully accept those characters as existing to be consumed. It becomes problematic when (the fan) cannot make this distinction or accept the reality a character's existence serves+

infatuation with fictional characters has generally been seen as normal and unobtrusive for people who fully accept those characters as existing to be consumed. It becomes problematic when (the fan) cannot make this distinction or accept the reality a character's existence serves+

about 2 months

1 replies60

📌

about 2 months

1

Definitely an interesting read. Bestie and I have lately encountered some toxic self-shippers/yumes. This pretty much sums it up. My bestie's a non-sharing self-shipper and I support her and my other self-ship friends because they're still "sober" about it. I'm more annoyed at self-shippers +

about 2 months

1 replies2

Pinksky is photo client for Bluesky.